The future of electric cars may depend on the deep sea mining of cobalt, and other critically important metals on the ocean floor.

That’s the view of engineer Laurens de Jonge, leading a major European investigation into new sources of key elements.

Demand is soaring for the metal cobalt – an essential ingredient in batteries of smart phones and tablets that have become the must have consumer item in the last 10-15yrs but crucially, with the rise of the electric car, so to have the demand on cobalt, and it is abundant in rocks on the seabed.

Laurens de Jonge, who’s running the EU project, says the transition to electric cars means “we need those resources”.

He was speaking during a unique set of underwater experiments conducted last year that are designed to assess the environmental impact of extracting rocks from the ocean floor and its effect on the fragile ocean eco system.

Could Coronavirus Be the Spark That Ignites the Industry?

No one predicted the global lockdown that happened in March this year and the devastating effects this has had on global trade with everything from tourism to retail feeling the brunt of the restrictions to population movement.

And whilst our towns and cities (through 90% and over reductions in road traffic) we are also experiencing cleaner air than we have measured since 1950.

Oil Costs Collapse

Oil supply is expected to fall to a nine-year low this month, the International Energy Agency has said, as global producers make big cuts to offset a record collapse in demand.

Last month, when a major Oil Futures contract expired, a frantic selloff among traders triggered a price slump deep into negative territory, with the benchmark at one point reaching -$38 a barrel.

But it isnt just transport, or lack of that has seen such a slump in the oil industry, which is expected to make tens of thousands of jobs redundant from May onwards.

The lack of manufacturing, fuelled by both s drop in demand due to coronavirus but also a lack of supply, in factories furloughing their workers, or restricting output to maintain lower employees working os as to maintain social distancing has also hit manufacturing hard.

This hit to manufacturing has also eroded the supply for oil, one of the core ingredients in plastics manufacturing.

Should Oil Mining Companies switch to Cobalt Mining?

This is a crucial question, both for the global economy, the energy sector, the car industry and anyway with an interest in more electric cars over pollution creating combustion engines.

Could the lack of demand for oil, the cleaner air we are breathing and a surplus oil mining workforce be re-tasked to deep sea mine for cobalt?

Surely it is a question worth exploring?

Yet, cobalt deep sea mining is not without its risks and Engineer Laurens de Jonge of EU’s Blue Nodules project discussed some of the challenges with the BBC.

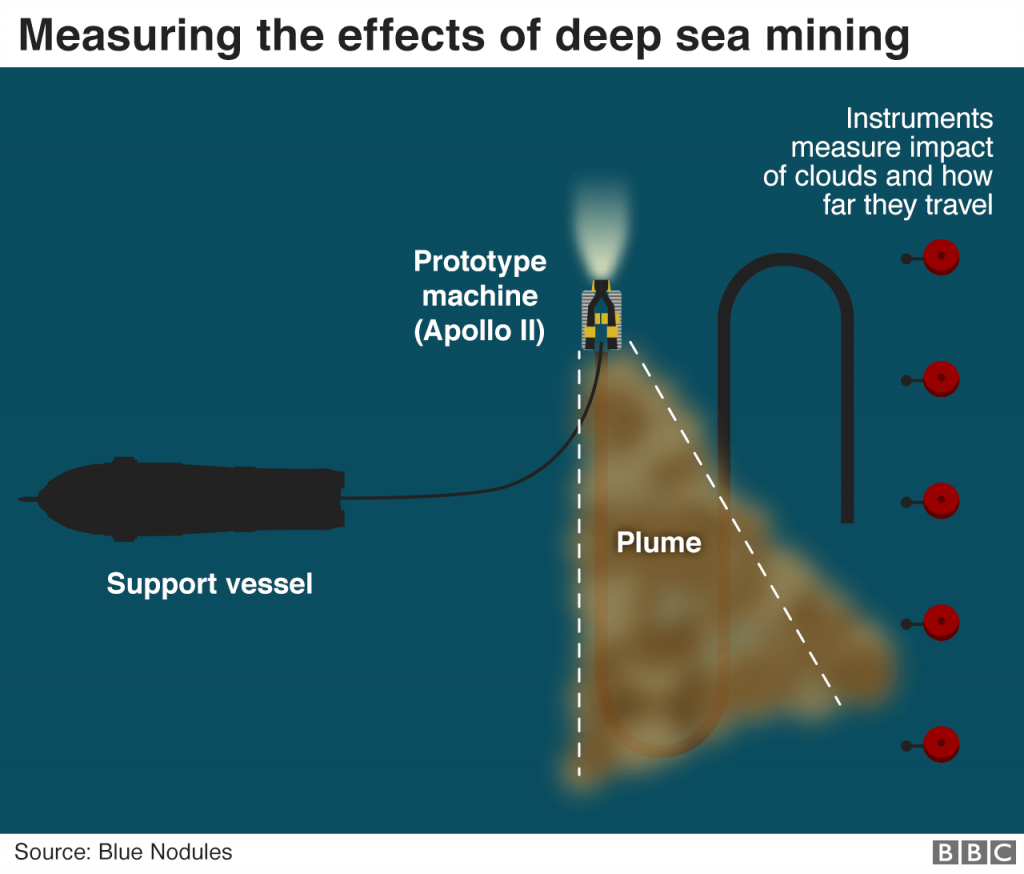

Laurens de Jonge explained that as part of his study an array of instruments were positioned nearby to a new prototype deep sea drilling machine (Apollo II) to measure how far these plum clouds from its operation were carried on the currents.

The risk of seabed mining smothering marine life over a wide area with its exhaust plume is one of the biggest concerns.

Why mine the seabed, for Cobalt?

There is no denying that there are vast costs and challenges in locating huge remote-controlled deep sea diving machines to the seabed to excavate rocks for the extraction of cobalt and whilst deposits do exist on land, there are political and safety issues involved.

Especially when you consider many of the world’s largest (on land) cobalt deposits are in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is the leading cobalt producing country, accounting for more than 60% of the world’s cobalt production of 140 million metric tonnes in 2018.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, where for years there’ve been numerous allegations of child labour, environmental damage and widespread corruption, the prospect of expanding cobalt production in Congo is clearly frought with its own challenges, which is leading mining companies to weigh up the potential advantages of mining cobalt on the seabed.

Whilst the concept has been talked about for decades, until recently it’s been thought too difficult to operate in the high-pressure, pitch-black conditions as much as 5km deep.

But now the deep sea mining technology is advancing to the point where dozens of government and private ventures are weighing up the potential for mines on the ocean floor, the EU project, Blue Nodules could be ideally positioned to stoke more interest in the technology and push for a swifter change from fossil fuel cars to electric.

EU Cobalt Seabed Mining Project Blue Nodules

Billions of potato-sized rocks known as “nodules” litter the nalmost endless seabed of the Pacific and many other oceans are also brimming with cobalt, so the aptly names EU project could well refocus attention from the deep sea oil mining companies.

Laurens de Jonge, who’s in charge of the EU project, ‘Blue Nodules’, said: “It’s not difficult to access – you don’t have to go deep into tropical forests or deep into mines.

“It’s readily available on the seafloor, it’s almost like potato harvesting only 5km deep in the ocean.”

And he says society faces a choice: there may in future be alternative ways of making batteries for electric cars – and some manufacturers are exploring them – but current technology requires cobalt.

Could deep sea mining be made less damaging?

Ralf Langeler thinks so. He’s the engineer in charge of the Apollo II mining machine and he told the BBC that he believes the new Apollo II design will minimise any impacts.

Like Laurens de Jonge, he works for the Dutch marine engineering giant Royal IHC and he says his technology can help reduce the environmental effects.

“The machine is meant to cut a very shallow slice into the top 6-10cm of the seabed, lifting the nodules. Its tracks are made with lightweight aluminium to avoid sinking too far into the surface.”

“Silt and sand stirred up by the extraction process should then be channelled into special vents at the rear of the machine and released in a narrow stream, to try to avoid the plume spreading too far.”

“We’ll always change the environment, that’s for sure,” Ralf says, “but that’s the same with onshore mining and our purpose is to minimise the impact.”

Some 30 other ventures are eyeing vast areas of ocean floor beyond national waters and which are regulated by a UN body, the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

The ISA has issued licences for exploration and is due soon this year, to publish the rules that would govern future mining.